I love engaging with people: it’s my passion. But if I couldn’t work with people then I would happily spend my life digging through archives looking for old documents and maps to find nuggets of incredible old stuff

Archives of thoughts

I’m on a train, on my way home from a day looking for documents in a county archive. On the face of it, what I was looking for wasn’t desperately interesting: ownership records of an old farm and the building of a bus depot. And yet, I’ve had a great time. It’s the wrinkles in the stories that you only get from looking at the original documents.

I’ve seen an advertising poster for the sale of cattle.

I’ve seen a plot of land described (by the estate agent) as “reputedly the most productive in this fertile district”.

I love that stuff. It’s the sense of the past being made up of the actions of real people in this case making up real estate agent nonsense in order to sell a farm.

particulars

More than that, I love looking at old handwriting. There’s something magical about holding a bit of paper that someone wrote on a hundred years ago or more. It’s as though someone’s writing has a little bit of their soul bound up in it. I get a real feeling of being in contact with an actual human being when I’m reading their handwriting.

Even if all they are saying is that they’ve included a cheque for the sum of…

Oddments and sodments

And then there’s ephemera. All the peculiar things that someone has, for whatever reason, decided is important to be kept for posterity. It can be sublime, like a bird’s eye view of Exeter, or the brochure advertising the launch of a new piece of municipal architecture.

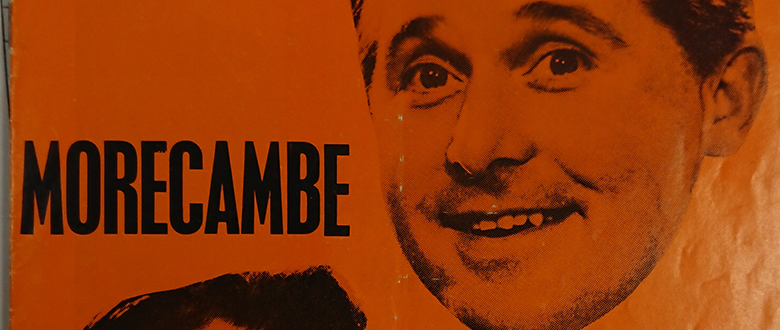

Or it can be the ridiculous. Why on earth did someone decide that the archives needed a flyer for a Morecambe and Wise gig?

morecambe and wise

Maps: archives in pen and ink

More than all of that, I love looking at old maps.

Sales particulars are a great source of old maps. They’re beautifully drawn pen maps with pastel washes for the properties in question. I get a real thrill out of trying to piece together where they are against the modern map, but they’re wonderful artefacts in their own right. I could go to an archive and just look at them all day. Maybe I’m a frustrated cartographer?

particular map

One of the oddest from today’s archives was half an Ordnance Survey sheet. Yup, that’s right: half a sheet. It was torn in two and the record office only had the upper half. What on earth happened? How did the map get torn? Was it an accident? Was it an argument? Had some kind of formally brokered deal between two people who both owned the map? And then, someone decided that this bit of a map should be deposited in the county archive. Why was that? Did they feel that this half an OS sheet should be kept for posterity? I was fascinated. My mind ran away with me thinking of all the interesting stories that could be woven around what was an, admittedly, unremarkable map.

Torn map

This kind of thing is oddly gripping.

Poking about

I’m a very lucky man that sometimes my job takes me to archives and record offices. My insatiable curiosity finds the whole thing fascinating. But I’m aware that not everyone has that opportunity, and that you have to be willing to spend a lot of time sifting through the unremarkable before you get to the memorable. I appreciate that not everyone, especially children, is prepared to do this.

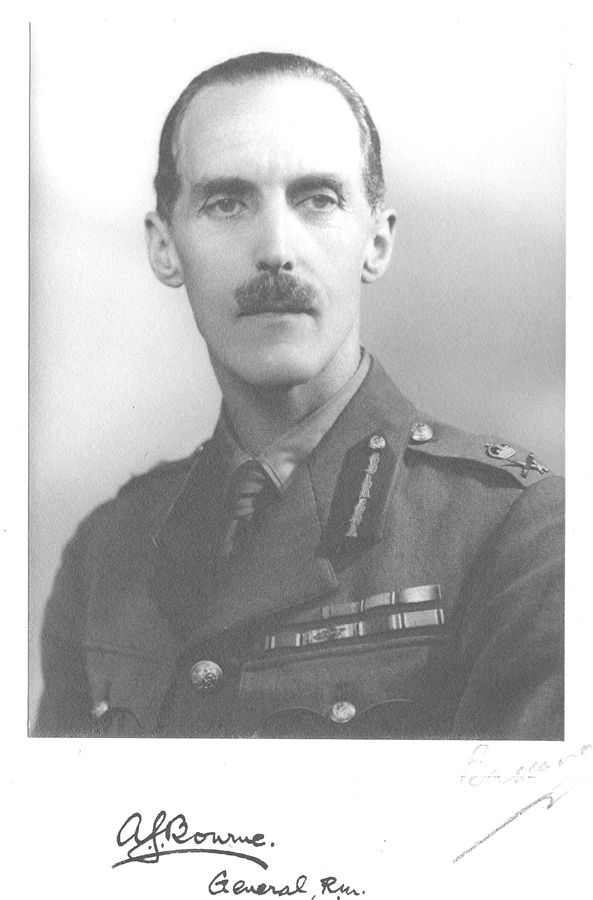

And that’s why I try to use archive material in Past Participants’ sessions. So, you can get the same thrill out of seeing someone come to life through their handwriting or a photograph. When we’re talking about someone from history, let me put their own words in your hands. Whether it’s their diary, a letter home to their mum or just an official note. It’s still like them speaking to you from beyond the grave.

There are few things that really drive home the point that these are real people we’re talking about than seeing a physical artefact of something they did. I get a huge kick out of the way children engage with it, even when they struggle with hundred-year-old handwriting.

And that’s cool. And that’s why I do it.

Call to archives action

This year’s remembrance sessions will use the actual words of two soldiers, who served through the final months of the First World War. It will be them telling the story of what being on the front line in those months was like.

One managed to get away physically unscathed. The other was less lucky, losing much of his right hand in the process. Hearing him talk about the process of being sent home from the war because of his wounds is a gripping read. Even when it’s told in a soldier’s understated language.

Get in touch and see about getting Past Participants in for Remembrance, and I can show you all the cool stuff that I’ll be bringing with me.